Before You Call It a Comeback

Refuting a proposition requires resisting knee-jerking and trying to fully understand it first.

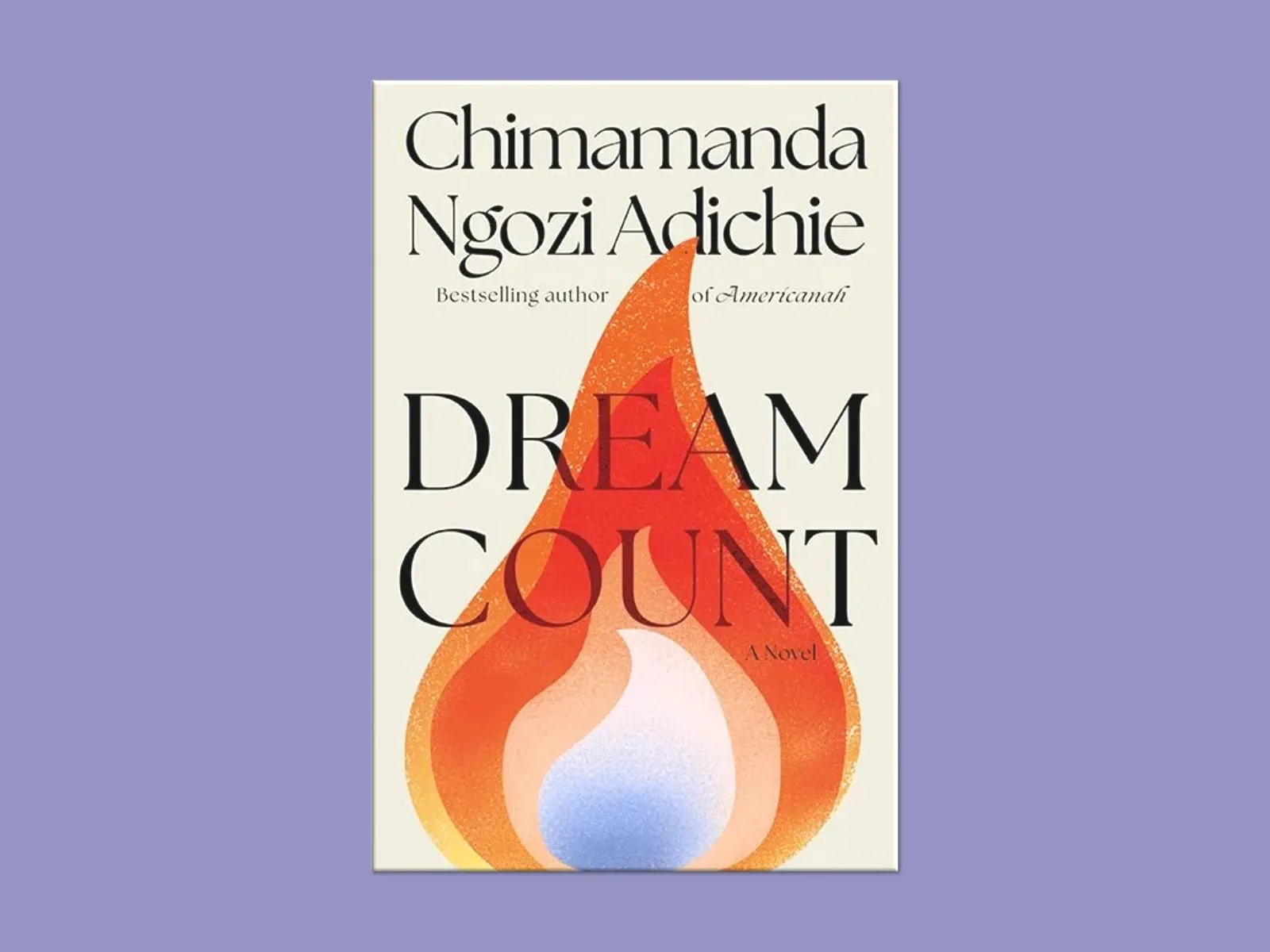

By Adebiyi AdedotunAfter several years of coming to terms with global fame, Chimamanda's new novel “Dream Count” has been ushered in with lots of rave and some reservations. It's her first novel in twelve years, since “Americanah.” Much of the buzz has celebrated this long-awaited novel from a writer whose simplicity and prolificacy have made her beloved by many. Her deserved growth and celebrity have attracted a broader audience, both at home and abroad, and her fame now exists independently from her literary work. In a 2018 New Yorker profile of Chimamanda, five years after “Americanah,” Larissa MacFarquhar captured this nascent separation of concerns. “As her subjects expanded,” she writes, “her audience would, too, until her celebrity became untethered from her books and took on a life of its own.”

Over the years, Chimamanda has become more than just another fiction writer; she has emerged as a thinker and thought leader from whom much is both given and expected. The foundation of her influence was built on her love for fiction, yet the imaginary worlds she creates have given way to real-world influence and responsibility. Crafting characters in novels is, however, unlike navigating the complexities of global politics and culture. Many now care as much about what she thinks beyond the covers of her books as they do about the stories within them, making her voice a powerful force in cultural conversations—both an opportunity and a burden.

We see this insistence all too well in the Vulture review of “Dream Count” titled “Don’t Call It a Comeback,” one not so much about the book itself as it is about Chimamanda's beliefs and ideology on gender, feminism, cancel culture, you name it. An official Vulture tweet for this review that is at once brazen and provocative succinctly reads, “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s new novel ‘Dream Count’ suffers from the retrograde gender politics and bad writing that has defined her career of late.” Which of the careers, you might wonder since Chimamanda has since become an outlier and a multi-faceted individual who refuses to be defined by the dangers of a single story. This is part of her allure that she can be simple yet unpredictable.

“Don’t Call It a Comeback,” an otherwise bad-faith review sprinkled with some valid points, examines the shrinking gap between Chimamanda’s celebrity and her recent literary work. It argues that this tension—between her public persona as a ‘pop-public intellectual’ and her role as an established author—has caused her writing to suffer. The conniving sequence in the aforementioned tweet—first “gender politics,” then “bad writing”—is significant because it dictates that the latter must be perused through the peephole of the former. Her writing is bad not in spite of her publicly espoused ideals—and her reconciliation with stardom—but because of them.

“In the 12 years since releasing her best-selling novel Americanah,” the review begins, “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has published prolifically but not primarily as a writer of literary fiction.” It continues, “Instead, she has ventured into other forms: memoir, children’s literature, feminist manifesto, a public lecture on free speech.” The public lecture mentioned here was the 2022 BBC Reith Lecture on The Four Freedoms—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—where Chimamanda lectured on the first of the quartet as it pertains to cancel culture, and “wokeness.”

There's a lot to unpack from the lecture and how it particularly applies to the review herein, but of note is that contrary to localized popular opinion and historical—both local and foreign—this kind of review isn't particularly surprising or unexpected. Presciently, another unsurprising reaction is many of the localized knee-jerk responses to the review: a complete blackout on its content. This denunciatory impulse may irrefutably seem plausible initially—after all, what might one learn—but I'd strongly argue to the contrary, solely because if there's one thing I've learned from Chimamanda, from reading her articles, watching her videos, and listening to her on podcasts, over the years, it is that she would want you to read “Don’t Call It a Comeback,” because as she puts it, “And I often say when I am feeling a little sanctimonious, that I am interested in the ideas of people who disagree with me because I believe that it is good to hear different sides of an issue.” But “Don’t Call It a Comeback” isn't a “different side” any more than it is a “one side.” Yet, Chimamanda's interest is rooted in her desire to “understand them properly and therefore be better able to demolish them.”

Disagreement, if not understating the reception, is normal. Worse is not understanding what we disagree with or the context within which such worrisome ideas sprouted. There's always something to learn, even if we find a material adversarial to our long-held beliefs—and there will be many in our lifetimes. What we must seek to achieve in tending to opposing voices isn't acceptance, it is filtering them down to their very essence, the one that challenges our preconceptions, after which we decide for ourselves what our new understanding must be, if any.